The Slowdown of Operations in the Panama Canal and the Possible Implications for the European Consumer

Miraflores Locks Panama canal-Taken on 1 May 2013,

Professor Dimitrios Dalaklis*

World Maritime University**

As I look outside the window of my office (in Malmö/Sweden), heavy rain is clearly standing out. In exactly the same viewpoint, a second quite distinctive feature of interest is the city’s canal system. As an important port through the course of history, Malmö is associated with a quite intricate network of waterways and canals -quite similar to Venice, or Amsterdam, but certainly to a much lesser extent. Although today these water corridors serve mainly touristic and recreational purposes, in the past they were heavily utilised for transferring goods and contributed into an elevated status as a hub for commerce. In any case, Christmas holidays are approaching fast; the various festive decorations indicate that interest of the consumers will be shifted toward buying presents for family and friends, no matter of the cold and rainy weather. After all, it is certainly expected that Europe and especially Scandinavia will experience weather patterns associated with heavy rain and snow during the winter season and the region’s water reservoirs (natural or man-made) will soon be completely filled with fresh water. However, at exactly the same time, in Panama -a very distant location across the globe that the average European citizen has a rather limited interest for and perhaps has not even heard of- it is exactly the lack of rain that is creating concerns for the immediate future.

More specifically (and with a little rounding up or down of the relevant figures), nearly 1,000 ships pass through the Panama Canal every month. These vessels are carrying a total of over 40 million tons of goods—about 5% of the world’s maritime trade volume. Unfortunately, water levels in this vital transport link (a real “shortcut” that is facilitating the connection between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by transiting one of the narrowest points of the American Continent) have fallen to critical lows due to the worst drought in the 143-year history of this extremely vital for maritime transport activities infrastructure. Panama, clearly one the wettest countries in the world, is currently experiencing one of its driest seasons on record. Cutting a long way short, the Panama Canal shortcut greatly reduces the time for ships to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, enabling them to avoid the lengthy, hazardous Cape Horn route around the southernmost tip of South America via the Drake Passage or Strait of Magellan. It is one of the largest and most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken.

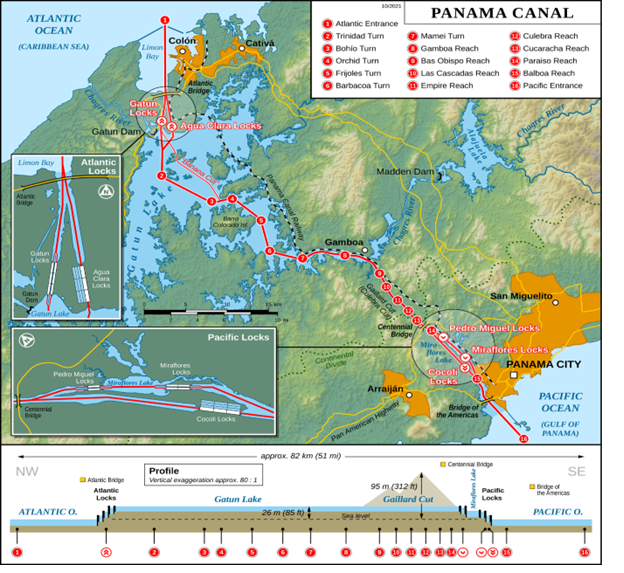

It is estimated that a figure close to thirteen to fourteen thousand ships pass through the canal each year, generating upward of $2 billion in revenue. The United States of America (USA) is the canal’s largest user; 40 percent of all USA container ships traverse it annually, carrying $270 billion in cargo. Other major users include Chile, China, Japan, and South Korea, since the Canal is serving mainly commerce needs between Asia and the Americas, as well as the seamless connection of the Pacific Ocean with the east coast of the USA. This artificial and quite complex interoceanic waterway has an approximate length of 82 km (51 mi), cutting across the Isthmus of Panama. A very innovative feature that is standing out in the build-up and way of operations in relation to this advance technical maritime infrastructure is that it uses a system of locks with two lanes, which operates as water elevators and raises the ships from sea level to the level of Gatun Lake, 26 meters above sea level, to allow the crossing though the Continental Divide, and then lowers the ships to sea level on the other side of the Isthmus (see Fig. 1).

To avoid lengthy details, these locks at each end lift ships up to Gatun Lake, an artificial freshwater lake 26 meters (85 ft) above sea level, created by damming up the Chagres River and Lake Alajuela to reduce the amount of excavation work required for the canal, and then lower the ships at the other end (see Fig. 2). Unfortunately, an average of 200,000,000 L of fresh water are used in order to facilitate a single passage, therefore maintaining of Gatun Lake well above a certain level is important for the normal operation of the Canal. Since freshwater serves as the basis for the Canal’s lock-driven operations and the recent lack of abundant rainfall is leading to lower water levels, the end result is a disruption on its normal operations pattern: Canal authorities have imposed restrictions on vessel weights and daily traffic. The Panama Canal Authority (ACP), the government agency that manages the waterway, began imposing water-saving restrictions earlier this year; another indicator of the complexity of the problem is that in addition to capping the number of ships that cross the canal each day, the ACP has restricted their maximum weight and draft, or how deep below the waterline a ship sits[1]. The restrictions imposed due to drought in Gatun Lake, the true blood line of the canal, have reduced traffic by about 15 million tonnes so far this year. And ships have been facing delays averaging six days. On the positive side, Authorities are already exploring various strategic options to boost water supply to the canal.

This is clearly another instance of a weather-impacted waterway slowing down the flows of critical freight. The shallower levels in the Rhine River in Europe, as well as the falling levels in another quite impart waterway for the USA, the Mississippi River, also clearly fall within the notion that climate change and shifting weather patterns can disrupt the flow of commerce and contribute into a raising inflation problem. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) more than 80% of our merchandise in trade is moved via vessel over the water; when you have a bottle-neck causing delays in one part of the supply chain, the rest of that chain is automatically affected. Whether driven by climate change/weather, geopolitics or some other unforeseen circumstance, any disruption relating to maritime choke points is creating troubles for the global supply chain networks and this in turn could translate into an increase final price for the end consumer. Although the direct impact to US manufacturers, retailers and consumers appears to be minimal right now, the potential for broader disruption is growing.

Normally, at this time of year, the lake levels in Panama are increasing. However, rainfall this spring and summer in the country under discussion has been the lowest since the turn of the century. Container ships, which have been prioritized, have not been significantly impacted by the introduction of restrictions. However, the biggest issue with the logjam concerns energy, with petroleum products being the primary commodities shipped through the canal. The canal under discussion has become the main way energy is moved from the east coast of the USA to China, India, Korea and Japan; all these countries are very significant players in manufacturing and will soon be faced with increased energy costs. There are estimates that a figure between 10% to 25 % of total maritime trade flows could be affected by the drought in Panama; in turn there will be ripple effects that will reach far away as Asia, North America and even Europe. The drought will hamper trade for the coming months, with crossings halved to 18 ships a day through February, from 36 slots that are available today. Economies that depend on the canal for trade should prepare for more disruption and delays.

Until recently, Panama was one of the world’s wettest countries; the 191 centimetres (75 inches) of rainfall it received per year provided plenty of freshwater for Gatun Lake and ensured the normal operation of the Canal. But meteorologists have pointed out that the return of El Niño, a weather pattern characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Pacific, is making the country drier and hotter. Total rainfall in Panama this year (2023) is already at historic lows and there are warning of even drier conditions for next year. Amidst climate change, droughts, floods, and various other disasters are becoming more frequent and pose a serious threat to existing maritime infrastructures. Policymakers should timely prepare for future disruptions in trade caused by shocks related to extreme climate changes and introduce as soon as possible the necessary measures to respond to them. Because of COVID-19, ordering patterns shifted from “just in time” to “just in case” and increased prices was the end result. Likely, at this point of time warehouses are already plumb full of products, and those inventory levels remain high enough, so there is no need to worry for your upcoming Christmas spending. But failing to mitigate the already identified risks, will make paying more for our next Christmas presents something like a self-fulfilling prophecy.

[1] To improve efficiency and number of transits available, a third, wider lane of locks was constructed between September 2007/May 2016. The expanded waterway began commercial operation on June 26, 2016 and allow transit of larger, NeoPanamax ships. Since the beginning of the 2023 dry season, the Panama Canal had adopted several water saving/conservation measures in the transit operation, including the use of water saving basins in the Neopanamax Locks and cross-filling in the Panamax Locks. However, the late arrival of this year’s rainy season, and lack of precipitation in the Canal watershed has recently obliged the concerned Authoritites to “formally” reduce the transit capacity.

*Dr. Dimitrios Dalaklis expertise revolves around maritime safety and security issues, including topics under the maritime education and training agenda.

**The World Maritime University (WMU) was founded in 1983 by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN), as its premier centre of excellence for maritime postgraduate education, research, and capacity building. The University offers unique postgraduate educational programmes, undertakes wide-ranging research in maritime and ocean-related studies, and continues maritime capacity building in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. See also: https://www.wmu.se/about/mission-vision-statement